On one hand, we spent maybe too much time this week on the question of whether one person should lose access to his social media accounts. On the other hand, it’s a question that illuminates some of the central tensions that led me to start this newsletter. How can social media be used to do harm? Can tech companies effectively rein in their worst users? Also, what the hell is Twitter’s deal?

Will Oremus tries to answer the latter question

with some reporting on what people inside Twitter are saying about Alex Jones. He offers a handful of theories on the company’s paralyzed, contradictory stances on Infowars. First, there’s Twitter’s bias toward inaction on almost all things; second, there’s its terror of being called partisan by conservatives or by Congress. There’s also the possibility that Twitter will ban Jones, and is still finalizing its public case for doing so.

Finally, Oremus concludes, is the possibility that there’s currently a big internal fight about Jones that hasn’t been resolved yet. This is my own theory, and here’s a smidge of evidence that it’s true. Yesterday I asked the company for comment on Oliver Darcy’s

damning report showing that, contrary to Twitter’s public statements, Jones had repeatedly violated the Twitter rules. The company told me a statement was coming, then never delivered. That’s the sort of thing that happens when a company is still trying to figure out its own position.

Mr. Zuckerberg, an engineer by training and temperament, has always preferred narrow process decisions to broad, subjective judgments. His evaluation of Infowars took the form of a series of technical policy questions. They included whether the mass-reporting of Infowars posts constituted coordinated “brigading,” a tactic common in online harassment campaigns. Executives also debated whether Mr. Jones should receive a “strike” for each post containing hate speech (which would lead to removing his pages as well as the individual posts) or a single, collective strike (which would remove the posts, but leave his pages up).

Late Sunday, Apple — which has often

tried to stake out moral high ground on contentious debates — removed Infowars podcasts from iTunes. After seeing the news, Mr. Zuckerberg sent a note to his team confirming his own decision: the strikes against Infowars and Mr. Jones would count individually, and the pages would come down. The

announcement arrived at 3 a.m. Pacific time.

Much attention has focused on how Facebook moved forward with a ban only after Apple did the same thing. To me, the preceding paragraph is just as noteworthy: it shows the company was already building its case for doing so when it kicked him off the platform. That speaks to

something I said Tuesday: that the platforms all seemed to be moving independently to the same conclusion, reinforcing one another’s decisions along the way.

A few months ago, during the rapid fallout of Facebook’s Cambridge Analytica scandal, a smart person mentioned to me the first rule of crisis PR. The idea is to quickly figure out what the ultimate end game of a disaster will be, and then cut all the bullshit and just jump straight to doing whatever uncomfortable thing you’ll inevitably have to do under duress days, weeks, or months later. I’ve been thinking a lot about that maxim the past two weeks as the platforms make declarations about Infowars as a legitimate publisher, followed by some hedging, then a bit of backtracking, some light finger-wagging, a short timeout, and finally an ominous suggestion that the publisher is on thin ice. All the statements, interviews, and bad press seems to be careening toward a particular outcome for Facebook, YouTube, and Infowars, and it seems as if everyone but the platforms knows it.

Facebook and YouTube have now careened all the way to that “particular outcome” — banning Jones — while Twitter is still contemplating the end game. I suspect the company will arrive at the same place its peers did eventually. The only question is how much self-inflicted damage it will sustain in the meantime.

DEMOCRACY

It’s about to get a lot harder to run your “We Love Texas” Facebook page from Moscow:

The new measures will require administrators of Facebook pages to secure their account with two-factor authentication and confirm their primary home location.

Facebook will also add a section that shows the primary country from where a page is being managed.

This weekend is the anniversary of the deadly United the Right rally in Charlottesville. Peter Aldhous examines how Russian trolls tried to amp up the conflict on Twitter as it happened. Among other things, they heavily promoted the usage of the word “Antifa,” which then caught on.

By the summer of 2017, the Left Trolls were mostly a spent force. But that’s when nearly 130 Right Trolls, which posed as Trump supporters, had their big surge, their output rising to more than 10,000 tweets a day until suddenly dropping away after Aug. 18 — presumably when Twitter banned many of the accounts.

Does the white nationalist movement sometimes called “the alt-right,” which can feel ubiquitous on social media, get too much attention? Emma Grey Ellis tries to count up its members:

In Charlottesville, the best estimates put rally participant numbers between 500 and 600 people. For context, that’s five times as big as any far-right rally in the last decade, but is still only a tiny fraction of what you’d expect from their (inflated) digital footprint.

It’s also two hundred times smaller than 2017’s March for Science, and a thousand times smaller than 2017’s Women’s March. All signs point to an even lower turnout for Unite the Right in DC.

A social media crackdown in Bangladesh is what actual censorship of free speech looks like, in case anyone is wondering:

Students who had been part of the demonstrations told BuzzFeed News they were terrified of arrest following the protests and were deleting any messages of support they’d posted online, while a photojournalist who was badly injured covering the demonstrations described the situation as chaos and said anyone with a camera had become a target.

Much of this fear rests on a loosely worded law passed in Bangladesh 12 years ago — widely referred to as

Section 57 — that allows for the prosecution of anyone posting material online that the authorities determine could “deprave and corrupt” its audience, cause a “deterioration in law and order,” or prejudice “the image of the state or a person.”

ELSEWHERE

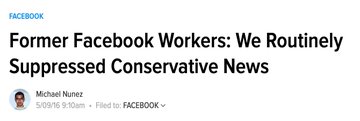

John Cook, former editor of Gawker Media, posts an odd “defense” of the 2016 Gizmodostory alleging that Facebook “routinely suppressed conservative news.” In it, he acknowledges that the story was framed in an aggressively conspiratorial way so as to draw the attention – and attendant clicks — of the Drudge Report audience. It confirms, rather than debunks, the idea that the story was framed in a misleading way so at to draw the maximum amount of outrage of conservatives, despite the fact that conservative news sources continue to draw more engagement than any other ideology on the platform.

Joshua Benton’s Twitter thread on how the Gizmodo story backfired says it all better than I can:

And while we’re once on the subject of “suppressing conservative speech,” here’s the monthly report from Newswhip:

Fox News retained its top position, with 38.6 million engagements, and increased its lead over second-placed CNN.

Facebook’s broadband and infrastructure projects have been reorganized into something called Facebook Connectivity, Rich Nieva reports. Here’s what project leader Yael Maguire said about the decision to stop building the internet plane Aquila, which crashed on its maiden voyage.

“I don’t think of it as a retreat,” Maguire said when asked about the decision. “If I wear the ‘I’m an engineer’ hat and I love to focus on the things that I build, yeah, maybe it’s a little disappointing what’s happening in the market. But if I take a step back as the person who’s focused on these efforts … it’s fantastic what’s happening globally with companies like Airbus and others who are focused on this as a potential market.”

Friend lists, which were automated feeds of posts from your coworkers, classmates, and so on, are going away for lack of use.

Relevant data point from Margaret Sullivan for the discussion around whether journalists can lead the charge against misinformation: employment in newspaper newsrooms has declined by almost 50 percent in the past decade.

David Marcus was on the board of directors at the cryptocurrency exchange Coinbase; recently he took over blockchain efforts at Facebook and the potential conflicts led him to quit Coinbase.

HQ, which has been slow to monetize, finally started showing ads this week.

LAUNCHES

One thing that AR is already very good at is showing people what makeup will look like on them. L’Oreal bought an AR company this year and plans to roll out shoppable makeup filters on Instagram.

TAKES

My colleague Laura Hudson examines the idea that journalists can effectively moderate Twitter by countering conspiracy theories with facts. This piece is very sharp and rather depressing!

A growing body of research has demonstrated that the distorted light of modern media does not always lead to illumination. In a

2015 paper, MIT professor of political science Adam Berinsky found that rather than debunking rumors or conspiracy theories, presenting people with facts or corrections sometimes entrenched those ideas further.

Another study by Dartmouth researchers found that “if people counter-argue unwelcome information vigorously enough, they may end up with ‘more attitudinally congruent information in mind than before the debate,’ which in turn leads them to report opinions that are more extreme than they otherwise would have had.”

A 2014 study published by the American Academy of Pediatrics similarly found that public information campaigns about the absence of scientific evidence for a link between autism and vaccinations actually “decreased intent to vaccinate among parents who had the least favorable vaccine attitudes.” When people feel condescended to by the media or told that they are simply rubes being manipulated — even by expert political manipulators — they are more likely to embrace those beliefs even more strongly.

Here’s a

Jack Dorsey-approved take from Mike Masnick on how Twitter should approach the Alex Jones question, with banning as an absolute last resort. Give people more tools to control what they see, he argues. (Counterpoint: platforms already do! Hate speech is spreading virally anyway, with deadly consequences.)

As for me, I still go back to the solution I’ve been discussing for years: we need to move to a world of

protocols instead of platforms, in which transparency rules and (importantly) control is passed down away from the centralized service to the end users. Facebook should open itself up so that end users can decide what content they can see for themselves, rather than making all the decisions in Menlo Park. Ideally, Facebook (and others) should open up so that third party tools can provide their own experiences – and then each person could

choose the service or filtering setup that they want. People who want to suck in the firehose, including all the garbage, could do so. Others could choose other filters or other experiences. Move the power down to the ends of the network, which is what the internet was supposed to be good at in the first place. If the giant platforms won’t do that, then people should build more open competitors that will (hell, those should be built anyway).

But, if they were to do that, it lets them get rid of this impossible to solve question of who gets to use their platforms, and moves the control and responsibility out to the end points. I expect that many users would quickly discover that the full firehose is unusable, and would seek alternatives that fit with how they wanted to use the platform. And, yes, that might mean some awful people create filter bubbles of nonsense and hatred, but average people could avoid those cesspools while at the same time those tasked with monitoring those kinds of idiots and their behavior could still do so.

Christopher Mims says it’s time to fight bots with bots:

While some attempts to detect social-media accounts of malicious actors rely on content or language filters that terrorists and disinformers have proved capable of confusing, Mr. Alvari’s algorithm looks for accounts that spread content further and faster than expected. Since this is the goal of terrorist recruiters and propagandists alike, the method could be on the front lines of algorithmic filtering across social networks. Humans still need to make the final determination, to

avoid false positives.

Algorithms could also be used to identify and disrupt social-media echo chambers, where people increasingly communicate with and witness the behavior of people who align with their own social and political views. The key would be showing users a deliberately more diverse assortment of content.

Whitney Phillips has some words of warning for journalists writing about QAnon and other insane conspiracy hoaxes:

The final question reporters must ask themselves stems from the fact that journalists aren’t just part of the game of media manipulation. They’re the trophy. Consequently, before they publish a word, journalists must seriously consider what role they’ll end up playing in the narrative, and whose work they’ll end up doing as a result.

In the context of the QAnon story, participants’ efforts to pressure, even outright harass, reporters into engaging with the story has been widely interpreted as proof of how seriously participants take the story, and therefore as proof of how worried we all should be.

MG Siegler explores the question of whether tweets should archive automatically the way Instagram stories do. (I think it should be an option.)

Still, it feels like having some optionality here with regard to the longevity of public tweets is the right call. I’m fine with leaving the default as “public forever” but maybe some tweets just make more sense for a moment in time… Or maybe some accounts would be happier letting tweets live for a certain amount of time by default. This isn’t an easy thing to think through, so I don’t envy Twitter on this topic.

AND FINALLY ...

Not having any luck on Tinder? Have you considered writing sonnets? Drew, a twentysomething educator living in Florida, did just that, charming his matches with poems that were also acrostics spelling out such Tinder-favorite pickup lines as SEND NUDES and WANNA SMASH. A Reddit post about his work is now one of the most upvoted posts of all time.

One poem actually led to a long-term thing. “I had a six-month relationship start from anonymous poetry shenanigans on Yik Yak as well as more than my fair share of Tinder dates from spontaneous sonnets written to order.”

Well, I know what I’m doing this weekend.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/60800601/acastro_180806_1777_facebook_0001.0.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment